Abstract

This paper examines the idea that contemplation of Christian martyrs can help alleviate the existential suffering of the conscious dying process, through an analysis of the 5th and 6th wood-cut illustrations of the Ars Moriendi, a 15th century manual on the art of dying, and Bill Viola’s 2014 polyptych video installation Martyrs (Earth, Air, Fire, Water). By analysing these artworks, produced 600 years apart, this paper will show both the consistency and potency of the idea that contemplating Christian martyrs can give consolation to those suffering in extremis, as well as highlight the universal constituents of the conscious dying process, particularly as it relates to existential suffering that remains relevant today.

To achieve the above-mentioned aims, this paper will begin by laying the foundation for the exploration of death-acceptance and eudaimonia in extremis (lit. happiness at the point of death) by introducing the idea of death-denial and its prima facie importance to such an exploration. It will then analyse death-acceptance as an outcome of a death-adjustment pattern, by exploring the work of Dr Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in relationship to the Ars Moriendi. Followed by an exploration of eudaimonia in extremis and its relationship to the Christian tradition of contemplating martyrs. After which, a detailed analysis of the Ars Moriendi will be undertaken, its historical and religious context, the text, an analysis of the short, illustrated version, paying particular attention to the 5th and 6th illustrations, in reference to the focus of this paper, i.e., death-acceptance and eudaimonia in extremis through the contemplation of Christian martyrs. The paper will then analyse Bill Viola’s Martyrs, in reference to the same above, ending with lessons that can be gleaned from such contemplation.

Key words: Martyrs, contemplation; death-acceptance, eudaimonia, in extremis

Introduction

Death is the great certainty in life, and knowledge of this certainty is the great defining characteristic of the human experience. Our knowledge of the death of all life, including our own, is, according to Becker (1973, p.27) both the source of human culture and the crux of our existential suffering:

“Everything that man does in his symbolic world is an attempt to deny or overcome his grotesque fate.”

Or as a response to Becker (Soloman, Greenberg and Pyszczynski, 2016, p. 123) elaborates:

“The supernatural cultural scheme of things that we humans embrace to manage existential terror is nevertheless ultimately a defensive distortion and obfuscation of reality to blot out the inevitability of death.”

The existential suffering brought about by the knowledge of our death typically reaches its zenith during the dying process and produces a consistent and recognisable pattern of psychological phenomena in the dying person. Also typical is the tendency for the dying person to become “stuck” in an aspect or stage of death-acceptance, thereby compounding their suffering. For this reason, much literature and art has been produced in response to and remedy for such “stuck-ness”.

The Ancient Roman artistic tradition of memento mori (Latin: remember you shall die), can be said to be a direct resolve to the denial stage of the dying process, which is a typical feature of death-acceptance models. Similarly, the Dutch 17thcentury vanitas still life tradition speaks to the over-attachment to and necessary relinquishment of worldly gain and glory in pursuit of a “good death”, again a feature of death-acceptance models, whether implied or explicit.

This paper will examine two works of art to assess their validity and usefulness as death-acceptance models, and guides to eudaimonia in extremis through the contemplation of Christian martyrs. The first being the Ars Moriendi, a 5th century medieval illustrated manual intended to guide a person through the dying process, to alleviate their suffering and bring them to a place of joyful acceptance, and necessarily, being a Christian document, a heavenly afterlife. The second is Bill Viola’s 2014 commissioned polyptych video installation Martyrs (Earth, Air, Fire, Water), displayed in perpetuity in Saint Paul’s Cathedral, London, which invites the viewer to imaginatively partake in a eudemonic response to end-of-life suffering and the consolation that the promise of death as the ultimate release from suffering will bring.

Before examining the death-acceptance and eudaimonia in extremis depicted in the Ars Moriendi and Viola’s Martyrs, it is worth clarifying and exploring what is meant by these terms.

Death-acceptance

Death-acceptance can be defined as a psychological state achieved by someone in the process of dying, whereby, they both understand and accept that they are dying. The psychological state of death-acceptance is typically achieved via a process, known as a death-adjustment pattern. The idea of a death-adjustment pattern, otherwise known as the “5 stages of grief”, was devised by Swiss American psychiatrist, Dr Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, in her seminal book “On Death and Dying” (1969, p. 9):

“The five stages – denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance – …are tools to help us frame and identify what we may be feeling. But they are not stops on some linear timeline in grief.”

Kübler-Ross’s death-adjustment pattern bears striking similarities to the stages of death-acceptance described in the Ars Moriendi (outlined below), pointing to either a direct influence on Kübler-Ross’s work, or evidence that the dying process and its attendant adjustment pattern has changed little in 600 years.

The desired outcome of both Kübler-Ross’s death-adjustment pattern and the Ars Moriendi is to bring the dying person to a place of acceptance, leading to a release from the existential suffering that knowledge of one’s impending death typically produces. Both Kübler-Ross and the Ars Moriendi agree that death acceptance is not a linear process, rather, acceptance is won by degrees as pertinent aspects of various stages in the process of dying, unique to the individual, are contended with and successfully overcome.

Although Viola’s Martyrs cannot be said to be a death-adjustment pattern per se, it can be read as a visual depiction of death-acceptance, therefore, can rightly be called a death-acceptance model. However, its true import is its acute depiction of eudaimonia in extremis, a feature too of the Ars Moriendi.

Eudaimonia in extremis

Eudaimonia is a Greek word that is typically translated as happiness, yet its meaning goes beyond mere happiness in the conventual sense, and embodies happiness that is meaningful, hard-won, divine in nature. In extremis is a Latin phrase, which translated means the furthest point or in extreme circumstances, but which is especially used to mean at the point of death, which extends to include the dying process as well.

Christian Martyrs are the exemplars par excellence of achieving eudaimonia in extremis. Their designation as martyrs – a Greek word meaning witness, referring to the legal act of providing witness or testimony – rests on their willingness to die as witnesses for their faith. However, it is not only for such willingness that they are singled out as contemplative icons to be admired and emulated when suffering in extremis. It is also for their ability to remain eudaimonic as grotesque tortures were visited upon them during the brutal taking of their lives, as described by the 4th century epistle, traditionally ascribed to the Church Fathers, regarding the martyrdom of St. Polycarp, Bishop of Smyrna (Schaff, ed. 1885, p. 66):

“Who can fail to admire their nobleness of mind, and their patience, with that love towards their Lord which they displayed? —who, when they were so torn with scourges, that the frame of their bodies, even to the very inward veins and arteries, was laid open, still patiently endured.”

Ars Moriendi

An examination of the Ars Moriendi model for death-acceptance and eudaimonia in extremis now follows. First with an outline of the text entire, then narrowing to a discussion of the second chapter, including an analysis of key theological terms found therein, and focusing on death-acceptance and eudaimonia in extremis through an examination of two wood-cut illustrations in the second chapter.

The Ars Moriendi is thought to be the work of an anonymous Dominican friar and was likely commissioned by the German Council of Constance between 1414-1418 (Dugdale, 2020 p. 33). The first version of the text, known as the “long version”, consists of 6 chapters, beginning with the consolation that death has a positive aspect and is nothing fear, followed by a detailed guide of the dying process, and ending with a series of prayers to be said for the dying person.

A shorter version of the Ars Moriendi, dating from c.1450, was also widely circulated. This “short version”, as it is now known, is essentially an adaptation of the second chapter of the long version, which outlines 5 temptations that assail the dying person and offers advice as to how such temptations might be overcome. From 1460, the short version was accompanied by 11 woodcut illustrations – 5 depicting temptations that assail a dying person, 5 depicting the overcoming of such temptations, and a final illustration depicting the triumph over temptation itself.

In this second chapter/short version of the Ars Moriendi (ed. Yakabuski, 2022, p.7) the author states that during the dying process a person has… “greatest and most grievous temptations, and such as they never had before in their life. And of these temptations five be most principal.” The temptations in question are infidelity, despair, impatience, vainglory, and avarice.

A Temptation in the context of the Ars Moriendi

Before discussing the temptations outlined in the Ars Moriendi, it would be beneficial to outline what is meant by “temptation” in the context of medieval church teaching.

A temptation is analogous to the medieval Christian conception of a sin, and yet there are several important distinctions to be made. A sin, properly understood, is rooted firmly in action, implies culpability, and has severe moral and spiritual consequences. Whereas, a temptation is rooted in the realm of the mind, resembling a thought rather than an action, and concerns a spiritual stumbling block rather than a source of moral degradation.

When framing a temptation as a thought or a mode of thinking, there is also a distinction to be made between our modern understanding of a thought and the medieval Christian understanding. Regarding our modern understanding, a thought is generally defined as a mental process emanating from within the thinker, whereas medieval Christian understanding defined a thought, of the type that manifests as a temptation, as a demonic entity that assails a person from without, (Tsakiridis, 2010).

A Temptation as a state of mind

A modern, secular interpretation of the Ars Moriendi conception of an end-of-life temptation, analogous to the medieval Christian conception of a thought, can best be described as a ‘state of mind’ – that is, a person’s mood or emotional state and the ensuing thoughts and behaviour that arise from such a mood/state.

The Ars Moriendi (ed. Yakabuski, 2022, pp. 7-14) details five such states of mind the assail the dying person, and although it is the third of these, impatience, that is the focus of this paper, it will be helpful to briefly outline all five states of mind to provide context for the proceeding discussion and a greater understanding of what a text like the Ars Moriendi was trying to achieve, namely, to provide a death-adjustment pattern, to guide a person to a place of death-acceptance and thereby facilitate of a good death.

- Infidelity or lack of faith – the rejection of one’s previously held religious beliefs, due to an overwhelming sense of fear, which can leave one vulnerable to delusion thinking.

- Despair – ruminating on all the wrong one has done in life leads to despair, which compounds one’s mental and physical anguish during the dying process.

- Impatience – the manifestation of anger and frustration brought about by the physical pain and mental anguish that typically accompanies the dying process.

- Complacence or spiritual pride – which overcoming the three previous temptations can imbue. This can engender a false sense of inviolability against the corruption of death, leading to a state of mind that can best be described as denial.

- Greed or attachment – to those things one has loved in life, be it family, friends, material processions, or worldly achievements, and the necessity of letting go of such things if one wishes to die well and limit one’s grief at the time of dying.

Ars Moriendi woodcut illustrations

The majority of ‘short version’ Ars Moriendi, widely distributed from the mid-15th century, were accompanied by a set of 11 woodcut[1] illustrations and were typically produced in a format known as block book, meaning both the illustration and text were cut from the same block of wood. The importance of the Ars Moriendi illustrations to its medieval audience cannot be overestimated. Far from being a mere visual enhancement of the text, they pictorially described it in great detail, thereby enhancing the reader’s understanding of the text, as well as, and more importantly, allowing the illiterate access to a text they would otherwise be denied.

Each illustration depicts a bed-bound man in the process of dying amid various personages and activities and banners containing Latin pronouncements relative to the given temptation. The first of each pair of illustrations depicts the dying man tormented by demonic beings, representative the pertinent temptation, and the second, the same man, having overcome the temptation and defeated the demons, is depicted in calm repose. The eleventh and final illustration depicts the man deceased and his soul ascending to heaven with the angles, with the demons writhing on the floor in defeat.

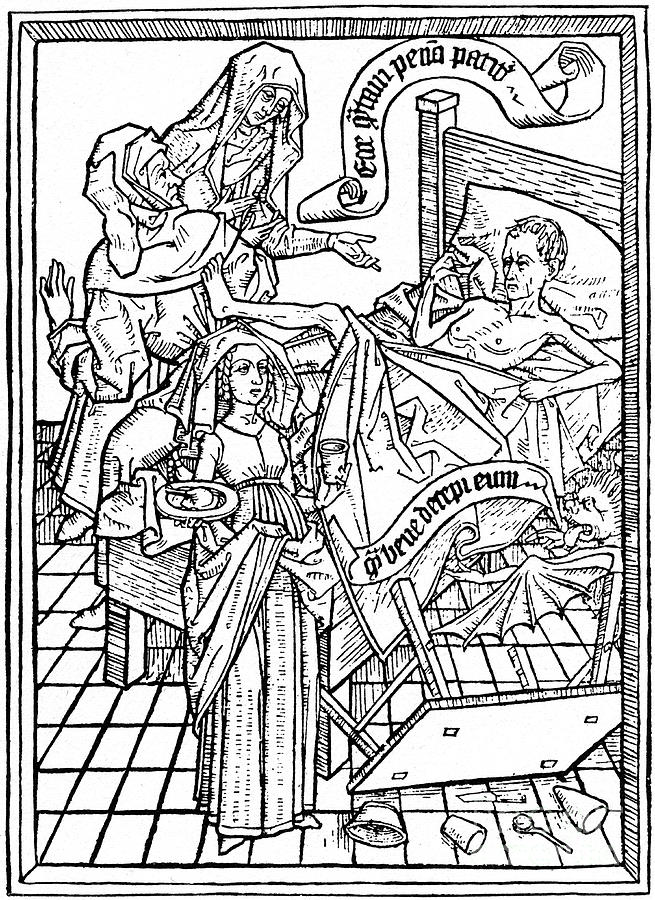

5th Illustration – The Temptation of Impatience

[1]

The 5th illustration of the short version of the Ars Moriendi concerns the temptation of impatience. It depicts the dying man in a rumpled bed, his face contorted with anger. His right leg protrudes from his dishevelled bedclothes and kicks a man, likely his doctor, in the back. A woman, likely his wife (or from a Jungian perspective, his anima, indicative of self-pity, no doubt a prevalent feature of impatience), her face full of compassion (or pity as the case may be), gestures to her husband and declares “Look how much pain he suffers”. A young woman, likely his daughter, at the foot of the bed, carries food and a beverage to lay on the bedside table, but stands motionless and bewildered as to what to do, as the table and its contents have been knock over, no doubt by the same flailing leg that is now kicking the doctor. Enjoying proceedings is a winged, lolling-tongued demon who declares “how well I deceive him”.

The text (ed. Yakabuski, 2022, p. 10) that accompanies the illustration describes the deleterious situation thus:

“For they that be in sickness, in their death bed suffer surpassingly great pain and sorrow and woe…those that be unprepared to die and die against their will…maketh so impatient and grutching,[2] that at times through woe and impatience, they become mad and witless.”

In sum, it is a scene of anguished suffering and impetuous anger. In this angry, frustrated state, the dying man lashes out at those trying to help him, but far from alleviating his suffering, it is making it much worse, both for himself and those in attendance.

6th Illustration – The Triumph Over Impatience

[2]

The 6th illustration depicts the dying man released from his anger, though his face still be etched with pain. God the Father and Jesus stand by his side, with Jesus holding a scourge in one hand to show that he too suffered, and in the other, a palm frond, symbolic of martyrdom. On the other side of the bed stands a guardian angel, likely a symbol of spiritual consolation. At her feet scurry two demons, one declaring “I am captured”, and the other, “I lost my efforts”. The dying man does not look at his consoling angel, neither does he look at God the Father or Jesus, rather he looks beyond them to the four figures stood at the end of his bed. They are the martyrs, and it is from them that his consolation comes.

The Martyrs

Each of the 4 martyrs depicted in the 6th illustration hold the symbolic and recognisable representation of their earthly suffering and death, which they accepted willingly and joyfully as a testament to their faith.

St. Barabara holds a tower, representative of the tower she was kept lock in by her maniacal father, the same father cut off her head after having her mercilessly tortured upon her refusal to renounce her Christian faith.

St. Catherine too had her head cut off, and prior to which she was to be tied to a bladed wheel, a grizzly torture that by a miracle was thwarted, but which prosperity still refers to as a Catherine-wheel, and which she still holds in most depictions of her, including the 6th illustration of the Ars Moriendi. In her other hand she holds the sword that took off her head, for her likewise refusal to renounce her faith.

St. Lawrence holds aloft a gridiron, on which he was tied and roasted alive. So complete was his consolation in his willing acceptance of his horrific fate, that tradition recounts that he cheerfully announced when he was sufficiently done on one side and suggested that his torturers turn him over to roast on the other.

St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr, barring Jesus himself, stands cradling rocks in his arms, symbolic of the rocks with which he was stoned to death. As the rocks rained down, so tradition has it, Stephen lifted his arms heavenward, asked forgiveness for those who were killing him, and then sunk to him knees and fell asleep.

It is no coincidence that the martyrs depicted in the Ars Moriendi, suffered the most degrading and excruciating deaths in all Christian martyrology. Further, in depicting the dying man looking not at God the Father, Jesus, or his guardian angel, but at the martyrs, alludes to the fact that it is not from contemplating divine beings that consolation comes, rather it comes from contemplating human beings. Human beings whose response to suffering in extremis, both bodily and existentially, serves as a testament that no matter the amount, grisliness, or degree of injustice of that suffering, it can be born.

It is this testament that Bill Viola likewise depicts in his work Martyrs (Earth, Air, Fire, Water), and to which we will now turn.

Bill Viola

Bill Viola (b.1951) is an American video artist, who works in close collaboration with his partner Kira Perov. Viola’s work primarily explores the most profound aspects of the human experience, such as birth, consciousness, spirituality, and death. He is most noted for his immersive video and sound installations which envelop the viewer. In 2003, Viola was commissioned to make two video installations to be on permanent display in the St Paul’s Cathedral, London. It took Viola several years to fulfil the commission, the result of which was Martyrs (Earth, Air, Fire, Water) in 2014 and Mary in 2016.

[3]

Martyrs (Earth, Air, Fire, Water)

Viola’s silent, polyptych video installation features four individuals across four vertical screens, each being martyred by one of the four cardinal elements earth, air, fire, water. The elements act as an overwhelming force upon the martyrs, against which they are powerless to withstand. However, during their ordeal, each martyr remains resolute and impassive in their suffering. Each video begins with a palpable stillness as the martyrs are introduced, subjected in some way that will make it impossible to resist the force about to be visited upon them.

Earth – a hand and the crown of a head protrude from a mound of dirt, that slowly spills upwards as a man rises in unison with the element that has already suffocated him. It is torment in reverse, made even more plaintive for its fait accompli.

Air – a woman is stretched, tethered by her hands and feet. The initial stillness reads as repose, but as time passes, an invisible force moves her; first in a gentle rocking motion, then thrashing violence. It is difficult watch, both for the invisibility of her tormentor, and for the anguished contortions of her body.

Fire – a man sits motionless on a chair, looking directly at the viewer. Warm globules of flickering light drip from above until the floor is scattered with puddles of fire that conflagrate and soar upward, engulfing the still motionless man, now surely a martyr.

Water – laying in the foetal position, a man is slowing hoisted into the air by his feet that are bound. Suspended, headfirst, arms out-stretched (reminiscent of St. Peter’s martyrdom), water begins rolling down his body, first drips, then cascade. Deluged and drowning, the man, now a martyr, exudes ataraxis.

As each element makes its presence known, the martyrs’ bodies become increasing intertwined with that force that abrades them, building in intensity until a crescendo is reached and the terminus of their Salvifici doloris (redemptive suffering) envelops the screen like a delicate explosion, at which point the viewer is released from the torment of partaking in their suffering. It is an elegant and deeply spiritual work, one that goes beyond memento mori, to challenge the viewer to think about the dying process itself and the isolating, all-consuming nature of suffering, and the choice one has to impassively endure it.

Lesson of the Martyrs

In Viola’s Martyrs, death is cast in the role of the four elements, thereby giving death – according to Palmer (1993, p.19) “a recognisable face”. The propensity to make death identifiable, helps a person to come to a place of death-acceptance, and is the result of the nature of death, which he describes as follows:

“Death is terrifying because it is omnipotent, omnipresent, and brutally impartial. At the same time, death is unknown and completely mysterious to us, a monstrous invisible presence threatening to take away everything we care about in an instant.”

In casting it in the role of the four elements, death, in Viola’s work, can be viewed as an indefatigable force acting upon the martyrs, which they are powerless to resist. This is a reasonable reading of the work – i.e., death as terror.

However, such a reading fails to consider the 2000-year-old tradition of contemplating martyrs in extremis, as depicted in the 6th illustration of the Ars Moriendi and innumerable artworks and texts besides. The lesson being death as hope…death as release. Read thus, the actual suffering of Viola’s martyrs is located, unseen, in the body, not in the elemental force of death impinging on the body from without. Instead, death is a benevolent, elemental force wrestling the martyr from their internal suffering. Ultimately successful in its task, death releases the martyrs from the constraint of their agonised bodies into eternal peace.

Conclusion

Unless one dies suddenly, or bereft of one’s faculties, the dying process will likely be accompanied with moderate to extreme suffering, whether physical, psychological, or both. Typically, one will wail and moan and writhe in reply; however, save a cursory analgesic effect in the moment, doing so will likely compound one’s suffering, rather than mitigate it, not to mention increase the suffering of those in attendance. Finding a way to be happy, or at least calm at the point of death, and the hours, days, or weeks that precede it, would not only be useful, it may also save one’s soul (or mind) from the ravages of suffering.

Of course, gazing on the mangled bodies of martyrs and their implements of torture and contemplating their stoic death-acceptance and eudaimonia in extremis is not for everyone. Indeed, for many it may seem a paltry, if not cruel and pernicious alternative to the pain-rescinding embrace of Morpheus or the narcoleptic glide of Pentobarbital. Yet respect is surely due those who resolutely avow to see life through to what may be the bitterest of ends, and for whom no alleviatory alternative is acceptable or available, save the knowledge that others have suffered the gross indecency of bodily and psychological torment before them, and kept their souls intact. This was the requisite case for the Ars Moriendi medieval audience, with the Age’s stark limitation of pain-relief and palliative care, let alone assisted-dying.

It may be true that the Ars Moriendi is an old-fashioned, therefore outmoded death-acceptance model, as well as an ineffectual stave to end-of-life suffering, in lieu of modern-day alleviants. However, the lesson of the martyrs, that of death as a beneficent force, as depicted in Viloa’s work, has substantive merit no matter how one chooses to navigate one’s dying process. Conceptualising death, not as the great taker of life, but as the great reliever of suffering, is the key to unlocking a positive attitude towards death and coming to a place of death-acceptance and, surely, consolation.

References

Becker, E. (1973) The Denial of Death, Great Britain: The Free Press.

Dugdale, L. S. (2020) The Lost Art of Dying: Reviving Forgotten Wisdom, New York: HaperCollins Publishers.

Kubler-Ross, E. (1969) On Death and Dying. London: Routledge.

Palmer, G. (1993) Death: The trip of a lifetime. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco.

Schaff, P. (1885) The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus. Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library.

Soloman, S. Greenberg, J. Pyszczynski, T. (2016) The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life. UK: Penguin Random House.

Tsakiridis, G. (2010) Evagrius Ponticus and Cognitive Science: A Look at Moral Evil and the Thoughts. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications.

Yakabuski, E. ed. (2022) The Craft of Dying: Ars Moriendi. Canada: St. Joseph’s Concordances.

Image References

[1] [2] University of California Press, Ars Moriendi: Blockbooks of the Low Countries. Accessed Oct 31, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft7v19p1w6&chunk.id=d0e3092&toc.id=&brand=ucpress

[3] Tate Images, Vilola, B. Martyrs (Earth, Air, Fire, Water). Accessed Oct 31, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/viola-martyrs-earth-air-fire-water-t14507

Bibliography

Aries, P (2000) The Hour of Our Death: The Classic History of Western Attitudes Towards Death Over the Last One Thousand Years, New York: Barnes & Noble

Becker, E. (1973) The Denial of Death, Great Britain: The Free Press.

Dugdale, L. S. (2020) The Lost Art of Dying: Reviving Forgotten Wisdom, New York: HaperCollins Publishres

Kellenhear, A. (2007) A Social History of Dying, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Kerrigan, M. (2007) The History of Death: Burial Customs and Funeral Rites, form the Ancient World to Modern Times, London: Globe Pequot Press

Kubler-Ross, E. (1969) On Death and Dying. London: Routledge

Langford, J. M. (2020) Death Rites as Existential Inquiry, Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Palmer, G. (1993) Death: The Trip of a Lifetime. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco

Pearson, M. P. (2003) The Archaeology of Death and Burial, Sheffield: The History Press

Schaff, P. (1885) The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus. Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library.

Soloman, S. Greenberg, J. Pyszczynski, T. (2016) The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life, UK: Penguin Random House

Tsakiridis, G. (2010) Evagrius Ponticus and Cognitive Science: A Look at Moral Evil and the Thoughts. Pickwick Publications

Yakabuski, E. ed. (2022) The Craft of Dying: Ars Moriendi, Canada, St. Joseph’s Concordance Collection

[1] Woodcut is a type of relief printing, whereby an image or text is created from a block of wood by removing negative space, leaving only the raised lines of the illustration/text. The raised lines are then inked, and the block of wood pressed against the printing surface, typically paper, revealing the intended illustration/text. Woodcut printing originated in China in the 7th century and spread to Europe in the mid-15th century, contemporary with the emergence of the Ars Moriendi. The Ars Moriendi, therefore, was one of the first printed ‘block books’ available in Europe.

[2] Grutching “to murmur, complain, find fault with, be angry”.